Stargate gRPC: The Better Way to CQL

Stargate gRPC: The Better Way to CQL

Stargate’s new gRPC API is so much more than just a feature release — it’s your official welcome to the “no drivers” future of Apache Cassandra.

Recently, we released gRPC as the newest API supported by Stargate, our API data gateway. On the surface, it would seem like the API doesn’t do very much; it receives CQL queries via the gRPC protocol, then passes those to Apache Cassandra® and returns the results. Sounds like a pretty modest feature release, right?

In reality, what the Stargate team has delivered is groundbreaking. Not quite a native driver and not quite a simple HTTP-based API, Stargate’s gRPC implementation represents a fundamentally new approach for applications interacting with Cassandra — an approach that’s more cloud native than any driver, and more performant than any simple HTTP-based API.

So let me tell you why this approach is so important, and why this is such a revolutionary solution for a common developer problem.

Native drivers are not cloud friendly

Functionality inside a native driver can be divided into two parts:

-

The query engine. This issues requests in a particular query language for a particular database, and receives responses to those requests that can then be used in application code. In our case, the query language is CQL, and the database is Cassandra.

-

Operational management. This includes tasks like connection pooling, TLS, authentication, load balancing, retry policies, write coalescing, compression, health checks, etc.

You’ll notice that most of those operational tasks are abstracted away from applications in cloud environments, and simply handled automatically on behalf of the application. For example, load balancing, health checks, and TLS termination are intrinsic to most cloud environments; even retries can be configured within the environment.

Put another way: in a well-designed microservices environment, network management tasks should live inside a service boundary and execute within an SLA defined in a service contract. There should be no need, and it would be a violation of microservices principles for an application to want to reach across that boundary and directly manipulate those operational tasks.

And yet, this is exactly what native drivers do.

This is not a mere architectural nicety. Building native drivers into an otherwise cloud-native, microservice-oriented application has real and negative consequences. Let’s dig a little deeper into why.

Native protocol drivers are expensive to maintain and require reimplementing the same complex functionality for different platforms (like Java, Go, Node, Rust). All that operational management forces developers to extend their skill set from application development in their preferred language to areas of systems operation, thus steepening the learning curve for native drivers.

More significantly, this co-mingling of concerns opens up a new vector that could trigger the need for a driver update. A configuration change in the network environment, for example, could require an update to the way every driver handles load balancing or connection pooling. Now your organization has to stop every application instance using that driver, apply the change within the driver, and restart all those application instances. Depending on the nature of the driver change, some changes in the rest of the application may also be required.

They also inject surprising brittleness into applications because of the network management overhead required, making it more likely that drivers, and therefore applications that use them, must be updated.

In sum, native drivers are:

- Complex and present a steep learning curve

- Hard to update and maintain

- Speed bumps for developer velocity

- A threat to application resilience

So we can safely say that native drivers are fast, which makes it easy to overemphasize raw performance, but the overall picture of performance and resilience is much more complicated.

HTTP-based APIs are a performance trade-off

The modern approach to application development is, in part, a rebellion against the burden of native drivers. Today’s application developers, particularly front end developers, are expected to interact with data through an HTTP-based API and rely on JSON as the primary method of structuring data.

We fully support this API-based approach on Stargate. This has several advantages:

- Language agnosticism. Applications can be written in any language that can talk to an HTTP endpoint.

- Separation of concerns between application environment and infrastructure environment. Precisely as should happen in a cloud-native context, all of the network management and operational overhead lives behind the API. Changes and updates there stay contained within that service boundary, removing this as an area of concern for application logic.

- Resilience. The statelessness of HTTP constrains application design to avoid reliance on durable network connections, meaning applications designed in this manner are more resilient against the vagaries of network behavior.

Unsurprisingly, HTTP-based APIs have become the backbone of microservice applications for a cloud-native environment. But these benefits are not free. HTTP-based APIs are a slower way to query a database, for two reasons:

- Networking - Native drivers talk “closer to the wire,” which significantly improves performance. The Java driver for CQL, for example, operates at Layer 5, whereas HTTP operates at Layer 7.

- Data transformation - Databases don’t store JSON natively (even MongoDB relies on the WiredTiger storage engine when you drill down far enough). So some transformation has to happen to turn a JSON-oriented query into a native database query (CQL, in the case of Cassandra). The compute overhead of performing this transformation further slows performance.

And now, we have a dilemma. On one hand, HTTP-based APIs offer simplicity and language agnosticism that accelerates developer velocity, while also offering a separation of concerns between application and infrastructure that improves application resilience. To put it simply, HTTP-based APIs are good cloud citizens, presenting and abiding by clear service boundaries.

On the other hand, while native drivers are a burden to developers and co-mingled concerns between development and operations negatively impact resilience, native drivers are just flat out more performant than HTTP-based APIs.

So, what to do?

Decomposing the driver

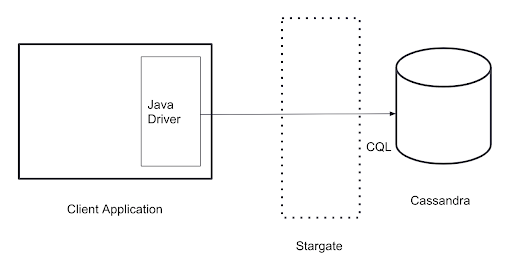

Stargate supports native driver calls, offering a CQL API through which to talk to Cassandra. This is essentially just a transparent proxy, and so CQL calls via Stargate remain highly performant. Let’s look at a simple architecture diagram of this part of Stargate. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1: Simple Architecture of Native Driver and Stargate.

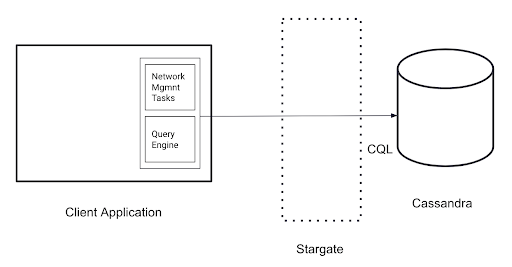

The fundamental problem is the co-mingling of concerns. Some of what lives inside the native driver should, in a cloud-native context, live behind an API and thus inside the API’s service boundary. So what if we looked at it this way instead? (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2: Decomposing the driver.

The real challenge is how to move that box that says “Network Management Tasks” across the service boundary into Stargate and behind an API. We’ll also have to do it in a way that honors the language agnosticism of APIs. Without that agnosticism, we have to maintain a different “box” of network management tasks for each language, even though those tasks are essentially the same across languages. We’d lighten the driver but make Stargate harder to maintain, and a good bit less cloud friendly.

Enter gRPC

In 2008, Google developed, open-sourced and released Protocol Buffers — a language-neutral mechanism for serializing structured data. In 2015, Google released gRPC (also open source) to incorporate Protocol Buffers into work to modernize Remote Procedure Call (RPC).

gRPC has a couple of important performance characteristics. One is the improved data serialization, making data transit over the network much more efficient. The other is the use of HTTP/2, which enables bidirectional communication. As a result, there are four call types supported in gRPC:

- Unary calls

- Client side streaming calls

- Server side streaming calls

- Bidirectional calls, which are a composite of client side and server side streaming

Put all this together and you have a mechanism that is fast — very fast when compared to other HTTP-based APIs. gRPC message transmission can be 7x to 10x faster than traditional REST APIs. In other words, a solution based on gRPC could offer performance comparable to native drivers.

Stargate gRPC

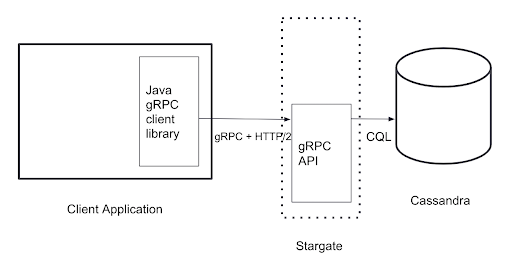

When you pull all of the network management tasks out of a driver, what you’re left with is a thin client library containing little more than the query engine. In our case, these CQL queries transit to a Stargate API endpoint via gRPC. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3: Stargate’s gRPC Implementation.

Behind that endpoint is what amounts to a CQL driver written in gRPC. In other words, it receives CQL calls on the API endpoint via gRPC, and then makes direct CQL calls to Cassandra. No data transformation is required, because we’re using CQL end to end.

These client libraries are dramatically easier to write and maintain. Our original intent was to launch with client libraries for Java and for Go, since these are our two most requested languages. As it happened, adding new languages was so easy that we also included client libraries for Node.js and Rust.

These four — and perhaps more languages in the future -— represent a fully DataStax-supported way to make CQL calls from your application. We’ll continue to support our existing native drivers, and in those languages the gRPC client libraries represent an additional, supported alternative. For languages like Go where DataStax does not have a supported native driver, the supported gRPC client library is now a great way to go.

Do more with Stargate gRPC

If your favorite language is not on our list, extending to a new language is not hard. From a protobuf file you get a skeleton of the CQL calls you need to make in your chosen language, and none of the operational overhead is required. You get that out of the box with gRPC, and it lives inside of Stargate where it belongs in a proper cloud-native context.

Thanks to bidirectionality and efficient data serialization, you’ll now get performance on par with native drivers combined with the simplicity of a thin client library, all within a context that plays nicely with the rest of your microservices.

To learn more, head over to Stargate’s Github. You can also find source code and examples on using Stargate gRPC API clients:

And, lastly, welcome to the “No Drivers” future of Apache Cassandra.